Whether you’re from a left or right perspective, you can probably agree that policymaking played some role in the Great Depression. If you’re of a right/libertarian view you might see policymakers as having lacked the mettle to force the economy into a deflated-price equilibrium (or, more accurately, to force the factors of production (pdf) to accept new equilibria) or simply to adhere to the agreed-upon principles of global economy (free markets, fixed exchange rates, a currency basis in gold, independent central banking …). And in fact this view was predominant in the post-war academic treatment of the Depression.

Then came the 1980s literature linking recovery to currency devaluation (pdf) (i.e. leaving the gold standard). This is the currently predominate view. The cornerstones are Lessons from the Great Depression (Temin 1989) and Golden Fetters (Eichengreen 1992). The latter in particular is an exhaustive treatment of the dynamics leading up to, and then transmitting globally, the 1929-33 depression. Temin and Eichengreen co-wrote a 2000 paper on the policymaking mentality sustaining poor choices (pdf). That article came to mind as I read Paul Krugman’s recent post about the Fed not doing enough to sustain the recovery. He used the frog-in-boiling-water analogy: if policymakers aren’t careful, they will wind up inadvertently presiding over a decade of stagnation. Temin and Eichengreen write that

The world economy did not begin to recover when [governing elites] changed their minds; rather, recovery began when mass politics in its various guises removed them from office.

How should we read that in today’s environment? The party in the White House is the party of the left. Will “mass politics” replace it with something further left? Unlikely (for now). What kind of policy “ethos” would mass politics produce from the party of the right? I think that’s a fascinating question. One way I like to frame policy choices is in the lens of the macroeconomic “trilemma”. This is the name for the inability simultaneously to choose your exchange rate and your monetary (and fiscal) policy amid free cross-border financial flows. Think of a few examples and you’ll quickly grasp it. If a country fixes the exchange rate but tolerates a little bit too much inflation (perhaps unemployment is high, so the central bank doesn’t want to raise interest rates, which it would otherwise need to do in order to kill off that inflation), then pressure will build on the currency peg: the rise in prices makes domestic output less competitive, so the trade balance starts to slip, which one day will break the peg, since you have to finance that trade deficit out of reserves. (I’m abstracting a lot here.) With free flows of capital, “one day” happens well in advance of the natural rate of attrition of central bank reserves. People see the writing on the wall and anticipate the collapse, thereby bringing it forward. (It was Krugman who formalised this.)

The Great Depression was an incredible laboratory of policy choices from among the trilemma. Policymakers had to run every which way to escape the vortex. So you had Germany and some of central-east Europe adopting stringent capital controls to keep up the façade of a pegged currency whilst pursuing strongly expansionary macro policy. You had another group of countries which stayed with the old-time religion of (mostly) open markets and fixed exchange rates. They didn’t need an independent macro policy because their one-off devaluation whilst crashing out of the gold standard left their economies quite competitive, meaning they spent the 1930s accumulating rather than spending reserves, which accumulations they could use to inflate the domestic money supply and therefore support recovery. (Global liquidity was boosted too by the USA revaluation of the gold stock in 1934.) Much less chosen were open capital flows, independent policy, and floating exchange rates — what we see among the rich countries today, mostly.

The United States issues the world’s numeraire currency. To an extent, that gives it a ‘free pass’ from the trilemma.The US can expand (or not) as much as it wants, while also having free capital flows and a fixed currency. “Hold it right there“, you say. “The US has a floating currency.” That’s actually not correct. The US may have a floating exchange-rate regime (i.e. the manner in which it manages the exchange market), but it does not have a floating exchange rate. A floating currency adjusts to the conditions prevailing in the economy, mostly. It’s a shock-absorber but also an enforcer. For example, if there’s a recession and growth is miserable, capital flows out to seek better returns elsewhere, and the currency slumps (and this slump makes the economy more competitive and possibly triggers recovery). By the same token, if you pursue reckless policy, the currency sells off and you pay the price in higher inflation.

Because the dollar is the global numeraire, a whole lot of people around the world buy and sell it for reasons that have nothing to do with USA domestic economic conditions. In addition to the mundane factors contributing to overall demand for the dollar in the global foreign-exchange market is one particularly pernicious if not outright capricious factor: liquidity flight. A.k.a. flight to safety or “running toward the fire when the alarm goes off” if you are looking at it from Peter Schiff’s viewpoint. Whatever you want to call it, the dollar surges when panic strikes.

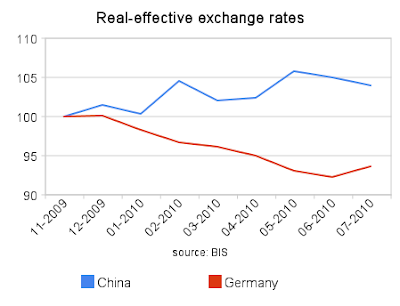

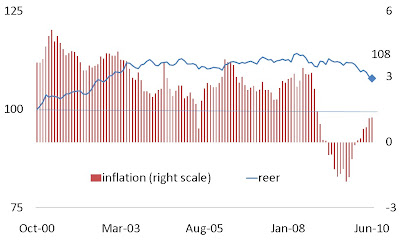

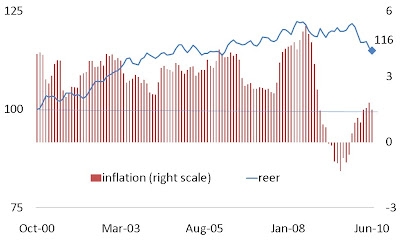

One can appeal to more direct grounds when claiming that the US dollar ain’t “floating”. Some of the US’s largest trade partners peg to it. Does anyone consider the USD/RMB exchange rate “floating”? No. Ditto the USD/riyal, the USD/TWD, the USD/KRW and so on. According to the Federal Reserve’s compilation of trade weights, these partners alone make up 30% of US trade. Bear in mind that trade weights, like much else in the world of economic analysis, are an artefact of a time when trade made up the majority of demand for the currency. We don’t live in that world. In our world, the foreign exchange market turns over a multiple of annual trade every few days. (Hence the influence of flight-to-liquidity when you’re the numeraire.) Bear in mind too that the current developing-world policy convention (the ‘Beijing consensus’) prescribes intervention in the fx market. When you read about accumulations of official reserves in Argentina, Brazil, Russia etc, keep in mind those reserves are predominately denominated in dollars. That’s not “floating”.

If you’ve any doubt that this is the inevitable price of being the numeraire, consider that this path has been trod before. The British pound sterling held that mantle in the 1930s. The parallel with today is striking. If you can get your hands on International Currency Experience (1944), the League of Nations’ autopsy of the global economy between the wars, have a look at Chapter 3, Section 4, “The Position of the Centre.”

When a great proportion of the available supply of Treasury bills in London was taken up by sterling-area central banks, less was left over for the clearing banks. The shortage of bills, if not actually deflationary, acted at any rate as a check on the expansion of credit. The effect was somewhat analogous to what would have happened under the orthodox gold standard, though obviously much weaker.

The operation of an exchange-reserve system such as the sterling area involves no doubt certain inconveniences to the reserve centre [the numeraire]. It has often been argued that, while the United Kingdom could not “go off sterling”, the member countries could obtain competitive advantages at the expense of the United Kingdom by pegging their currencies to the pound at an unduly low level.

What Giscard d’Estaing described as America’s “exorbitant privilege” in the 1960s was Britain’s too, before the war:

The other distinctive element in such a system … has this consequence that any deficit in the centre country’s balance of payments with the member countries, reflecting an overvaluation of the centre currency in relation to the members, tends to be covered by an “equilibrating” inflow of funds into the centre in the form of an increase in the member countries’ exchange reserves. … It is clear, however, that a persistent and excessive undervaluation of member currencies must after a point become objectionable to the centre country.

Moreover,

… the fluctuating balance of payments of the member countries (was) capable of rendering the centre vulnerable to international disequilibria in which it was not otherwise concerned.

The USA doesn’t have a currency policy because it can’t have a currency policy. This tedious exposition may in fact reveal something about the policy options for the next occupant of the White House, or of the party next to control the House of Representatives. Perhaps he/she/they will consider changing the rules. It’s akin to the Temin/Eichengreen quote: if the incumbents are passive, the insurgents get a look-in. Passivity in the US economy’s relations with the global economy might not be tolerable much longer. What does that mean? Probably the ‘un-thinkable’: a US tariff. It’s no novelty. It’s as American as apple pie. It was used to great effect the last time the US decided forcibly to wean the overdependent suckling economies off of its economic tit. Nixon in 1971 imposed a unilateral 10% import surcharge in tandem with taking the US dollar off gold, to shake off the stubborn pegs of countries which by all rights had otherwise outgrown such a developmental stage of policy. (Think of it as a political-economy problem. Particular domestic constituencies in the pegging country benefit from the peg. By definition, they are prevailing. Changing that political/policy equilibrium is very difficult from within (1/). The US tariff in 1971 was a nudge, a shove.) Nixon was following a distinguished tradition. FDR’s dollar shock in 1933/34 had a similarly rejuvenating influence on the populace and the economy, albeit for differing reasons.

The trilemma gets interesting when the US economy loses numeraire-currency status. For one thing, domestic US politics has never had to deal with this. The trade-offs imposed by the trilemma are real and, by definition, some constituencies and ideologies will be aggrieved. I am not a zero-sum thinker but the trilemma is something you cannot escape (unless you’re the numeraire).

Notes

1/ There is no solace in examining the outcome when the US was the premier global exporter, akin to China today. This was the interwar period. What the world needed desperately was a US economy as capable and willing to run an occasional trade deficit as it was a surplus. But the US economy wasn’t that way inclined and neither were its managers. A trade-surplus mindset was firmly implanted and nothing shifted it. Nothing, that is, except world war. It was only amidst that conflagration that the US policy establishment took a hard look in the mirror and asked, What happened? The answer is a 1943 publication commissioned and published by the US Department of Commerce, written by a private economics consulting firm called Hal B. Lary and Associates. (The citation is Lary, H.B., The United States in the World Economy: The International Transactions of the United States in the Interwar Period.) You won’t find a drier piece of reading nor one as illuminating in this respect. It is a mea culpa for the US role in the interwar depression. I gave a talk here recently to a delegation of banking executives from Shanghai, on the prospects and requirements of a ‘global currency’, which the renminbi will become. I mentioned the Lary publication and urged them to consider their own views about China’s role today and whether it might be repeating the US’ own policy experience. Which of course is its right. The US currency was no less pegged between the wars as China’s is today, and that was seen very much as the sovereign’s prerogative. Which it was and is.