Consider the travails of the euro-area in terms of the macroeconomic policy trilemma (1/). Here is the framework:

Framework for understanding the euro-area crisis

As a macro framework for analysis, consider the travails of the euro-area in terms of the macroeconomic policy trilemma (1/). Here is the framework:

i. Balance of payments trouble when external credit dries up (sudden stop) ==> solvency threat via banking system and sovereign debt via lender-of-last-resort / contingent debt.

ii. Maintenance of the existing monetary order (the system of irrevocably fixed exchange rates) is conflated with the preservation of society itself (e.g. Angela Merkel in May 2010 conflated euro-zone integrity with the existential status of the EU.)

iii. In fealty to (ii.), pursue austerity. In trilemma terms: adjustment is attempted on the backs of taxpayers/ workers.

iv. Monetary non-neutrality (2/) makes deflation a highly unlikely solution both to debt and competitiveness problems.

v. Repeat (iii.) until …

vi. Political upheaval or solvency crisis (the official lending stops and the sovereign cannot raise funds on the capital markets).

vii. Adjustment comes in one or a combination of the following:

a) Devaluation (for competitiveness, to achieve external surplus) and default (partial or total; also to achieve external surplus).

b) Capital controls (first on current account, then covering all transactions). Note that capital controls can be instituted precisely in order to repay external creditors; it is a way of marshalling all available foreign exchange for that purpose.

c) Trade barriers

Note that c) is really just a version of a) for those unwilling for several reasons to part with the irrevocably fixed currency regime. Does this suggest that if euro-area is unable to countenance disintegration (new currencies), then trade barriers and/or capital controls are next? Maybe not as crazy as it sounds.

Commentary:

notes:

1/ The trilemma is the recognition that policymakers cannot simultaneously enjoy all three of the following: fixed exchange rate; policy independence; and currency convertibility.

2/ In order for deflation not to be injurious, money must be ‘neutral’ — in other words, real effects must be indifferent to price increases and declines. The reality is that, with a few notable exceptions (Hong Kong), money is almost never neutral. For example, deflation might well contribute to insolvency through heightening the real debt burden and unemployment by raising the real wage. Workers DO accept eye-watering wage cuts but never on the order required to achieve competitiveness for the economy. Remember, in a balance-of-payments crisis, the economy needs to shift into a surplus, not just a balance. The implied adjustment in the real exchange rate is sizeable. Unless you believe in the “immaculate transfer”.

Intelligence squared debate: On the role of government in a recession.

The website is http://intelligencesquaredus.org/.

Nouriel Roubini comes out very well in this. Thank God he is on this panel. Laura Tyson engages with the supply-siders on their own terms — “the government must balance its books, just like households do” (I am paraphrasing). The job of a well-trained and well-historied economist is to explain exactly the falsity of this assertion.

The government budget is not like the household budget. The central government is the public coming together to accomplish things that cannot be accomplished alone. (The concept of ‘public goods’.) And NOW is the time for the central government to exercise that role. Ironically, it can borrow now much more cheaply than during ‘normal’ times. This makes it fiscally ‘prudent’ for the government to launch big infrastructure and education projects during a recession, that will have positive returns for the economy and the society. Moreover, in doing so, the government can assume the role that is normally played by the firm or household in the economy (being a borrower and spender), since those sectors of the economy are focused intensely on balance-sheet repair.

What amazes me is how we have lost this knowledge and experience gained from the Great Depression.

Update on euro-area periphery adjustment

|

Greece

|

Ireland

|

Italy

|

Portugal

|

Spain

|

|

|

Inflation (HICP)

Feb 2011 |

4.2

|

0.9

|

2.1

|

3.5

|

3.4

|

|

Labour costs

2010q4 |

-6.6

|

-3.1

|

1.8

|

4.2*

|

-0.8

|

|

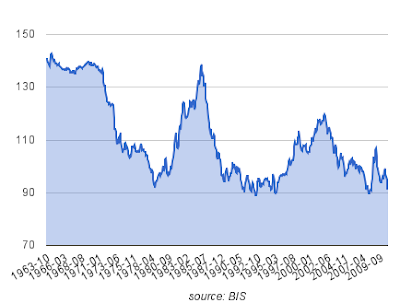

REER (BIS)

Jan 2011 |

-0.8

|

-5.9

|

-4.5

|

-1.5

|

-2.6

|

sources: Eurostat; national authorities.

all figures are percent y/y

* 2011q1.

Note:

euro (vs usd) change Jan2011/Jan2010 is -4.0%.

euro (NEER; BIS) change Jan2011/Jan2010 is -7.8%.

Since this issue is back on the boil with a pretty stern message from Germany in advance of the next instalment of official discussions to alleviate the woes of peripheral euro-zone members, i.e. those in the table above, it’s time to revisit some indicators of adjustment in the affected economies. What the data above tell me is that euro weakness — particularly on an effective basis — has been doing most of the work of getting prices down in these economies vis-a-vis rest of world. Inflation rates are stubbornly high and only in Greece and Ireland are labour costs falling. Note also that, for Greece, the improvement in the real exchange rate is minimal. One concern this all raises is the impact of a rally in the euro.

Glossary: “Effective” means trade-weighted, i.e. the exchange rate of the euro against all of its trade partners.

USA risk: Alert – Fed could surprise markets with further easing in 2011

My article on the prospect of an unexpected Fed easing in 2011H2 is now available on the EIU ViewsWire.

Central bank orthodoxy is under threat

My new article on QE is freely available from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s “Views Wire”: Central bank orthodoxy is under threat.

Four points against the conventional wisdom

1. Eurozone breakup is bullish.

The conventional wisdom sees eurozone breakup as calamitous. This view has even been supported by scholars who should know better. In my private discussions with “2nd tier” scholars (i.e. people well below the radar), our only conclusion is that these high-profile scholars are trapped. They’re in a predicament familiar to the credit ratings agencies: if they pronounce on the inevitable breakup of a currency regime, they bring that day forward. Imagine the weight of responsibility. So, here’s the question: What would you do if you knew that eurozone breakup was bullish but that you would take some of the blame if your pronouncement helped bring that about? I’m leaning toward integrity in life in general. You should say what you think, be damned the consequences. Will things get better if you keep silent? Of course not. The longer this predicament is left unresolved, the more misery endured.

To the mechanics. Euro breakup will reset national prices to a level that makes the economy’s traded sector competitive. These economies no longer can rely on growth in the non-traded sector. This is not a zero-sum question: a group of growing economies will specialize in different items; their growth will generate demand for each others’ output and services. Will it be difficult? Yes, of course. But it won’t be the calamity envisioned by some. And for the close neighbours with floating exchange rates (think UK or Turkey), what would you choose for these benighted eurozone members: A moribund neighbour locked in terminal deflation and inactivity (recession), or a rebounding one? Your exchange rate can offset some of the shock from their re-introduction of national currencies. Number 10 Downing Street should think carefully when it lines up behind Berlin-Paris in support of ‘rescue’ packages that lock these countries into interminable decline, rescuing only their creditors. (To be clear: I have no moral opinion on the euro. In fact, I love the spirit of it (not to mention the convenience). And I am all for the EU and the ‘European project’. What we must not do is conflate the European project with the euro itself.)

2. Reserve currency status for the US dollar is a poisoned chalice.

Most commentary on the US dollar’s international value treats reserve currency status as something precious, to be safeguarded at all costs. First, to clarify: “reserve” currency status is a bit of a red herring. For the most part, a currency is appealing for a reserve asset if its price against your currency is a target of policy. In English: if you are worried about the US dollar exchange rate against your own currency (let’s say, Brazilian real), then you intervene in the real/dollar foreign exchange market. And you accumulate/decumulate dollar reserves. You don’t hold dollars because they are the world’s best reserve asset; you hold them as a byproduct of your exchange-rate regime. So when you hear about “reserve” currency status, think instead “numeraire” currency status, because it’s the dollar price of your economy’s output that matters. International trade is overwhelmingly quoted in US dollars.

When you hear that the dollar’s international status must be preserved, you must ask, For whom? Let me cut right to the chase. It’s good for the financial services industry. And just as the US financial services industry has become politically influential, so too did that in London (where it’s known as “the City”, akin to “Wall Street”). The City can be found standing behind a number of critical junctures in UK currency policy, which proved difficult if not disastrous for the real (i.e. non-financial) economy. This is true of going back on gold at an unrealistic exchange rate in the middle 1920s and entering into the Exchange-Rate Mechanism, the forerunner of the euro, in 1990. That there is still a UK manufacturing sector is testament to some incredible resilience in UK manufacturing. And make no mistake — there is still a vibrant UK manufacturing sector. My point is that it’s been an uphill battle with an overvalued currency, and too much of the country reflects the blight of an abandoned productive heritage. Some very high proportion of working-age UK adults outside of the London/Southeast-England region are on a government payroll in some capacity.

Reserve currency status (really, “numeraire” currency status) is a poisoned chalice. The financial services sector likes it, because it wants to intermediate the world’s capital flows. But the price is high for important parts of the rest of the economy. If this can be relinquished anytime soon to the Chinese (fat chance), so much the better. (What does it say that the leading Congressional advocate of a stronger Chinese currency represents Wall Street? It says to me that dollar strength is secure with Congress. In other words: don’t believe for one second that Congress will be led into a robust currency confrontation with China. The US financial services industry has no desire to see this.)

3. Quantitative Easing by the Fed is covert US exchange-rate policy. It’s a good move but insufficient.

The conventional wisdom is concerned that the Fed’s purchases of long-term assets, dubbed quantitative easing, will “debase” the dollar. The reality is that this would be a good outcome. If the Fed, through QE, can push down the dollar’s international value, that’s a godsend for this economy. QE is Washington’s only exchange-rate policy instrument. Because the dollar is the global numeraire, most currency pegs are pegs to the dollar. This goes beyond the explicit pegs like Hong Kong; it includes the de facto pegs like China and the heavily interventionist regimes in East Asia and beyond. The particular exchange rate between the dollar and any of these currencies is not “floating”, no matter what US currency policy is (it’s “floating”). What can the USA do about these policies?

- International agreement is a non-starter. No amount of moral suasion from the IMF is going to change these countries’ currency policies. The plain truth is that the only semblance of an international currency agreement is the IMF’s revised Articles of Agreement. These enjoin member economies not to engage in policies that explicitly promote their balance of payments position. The burden of proof here would be too difficult to take seriously. International law in this regard simply does not carry the weight that it does in trade, for example. Nor should it. The currency is a sovereign matter and it’s for each country to decide how to manage theirs. The USA has almost never been willing to manage its economy in a way to serve some currency purpose. Why should it expect others to? In fact, attempts multilaterally to coordinate currency policies have often had undesirable consequences. The 1985 Plaza Accord is one, with unappealing consequences for Japan. This is a big reason why Beijing is not keen to put its currency policy in a multilateral framework. (The Fed in 1928 agreed to reduce US interest rates in order to alleviate pressure on the pound sterling. Again, the consequences were unfortunate. This policy poured fuel on the fire of a gigantic US stock market bubble.)

- How about a unilateral import surcharge? Nixon did it in August 1971 partly to strong-arm US trade partners into revaluing their pegs to the dollar. It worked.

- Quantitative easing. If worries over the effect of QE on the US money supply underpin a flight from the dollar, so much the better.

So QE is a good move as an exchange-rate policy. In most other respects it’s insufficient. The Fed is being incredibly conservative. It is buying only government bonds. And its efforts reach only as far as the banking system, which is not intermediating credit right now. The only money the Fed is capable of generating is “central bank money” aka “base money”. The only glimpse you have of this is the cash in your wallet. Period. Think of all the financial assets you own — bank account, savings account, retirement account, etc. None of this is central bank money. If you are in good financial shape, then cash is a very small fraction of your wealth. If you are in bad financial shape, then cash might in fact be pretty big for you. (Keep in mind that cash here does not include the loose usage of the term, i.e. money at short-term in the money market or in a checking account, which is often referred to as “cash”.)

So far, the Fed has not put cash in your hands, but it could. Right now, the central bank money being created by the Fed is being credited to the banking system’s deposits at the Fed. This money can be used by banks as the foundation for lending. But the banks don’t want to lend and the private sector doesn’t want to borrow. In other words, QE is pushing on a string. Yes, it might be pushing down interest rates on the assets it buys, and that’s a good thing. But it is not injecting new money into the non-financial economy, so long as the money it creates sits in reserve at the central bank.

4. Much economic commentary in the USA is stuck in the status-quo ante.

Much of the punditocracy is still thinking in status-quo-ante terms. In other words, all the indicators that signalled growth before the crisis continue to be treated the same way today. The easiest way to think of this is in a relative-price framework. Before the crash, arguably for two decades until the crash, growth was centered in non-traded activities. This was credit-fuelled and foreign-capital-fuelled. It meant that consumer spending equalled growth, never mind that the local content of those purchases went down and down. It meant that housing was a driver of the economy. It meant that Wall Street earnings were a bullish indicator. Housing and Wall Street are key non-traded sectors. They draw in resources from abroad.

That game is up. Growth will need to come from traded activities. Propping up US house prices does not support this transition — it stifles it. Propping up the financial services industry does not support this transition. So when you hear about the latest housing or consumer credit report, ask whether the way it’s being interpreted is appropriate now or for the status quo ante. My guess is you’ll hear a lot of the latter. This raises the question: what policies could the US administration be supporting to emphasise the transition to traded sectors over non-traded? As mentioned, QE is one — though it is a policy of the Fed. Another would be a different approach to housing. The administration should not seek to prop-up prices; it should seek to salve the balance sheet consequences of price decline.

One might ask, what is the traded sector? The key thing is to keep in mind the purposeful use of the word “traded” sector rather than “exports”. The boost will come in large part from a diversion in spending to US output. This is plausible. Start with the easy part. A weaker dollar will divert some tourism money away from overseas and toward the USA. It will divert some spending toward US-based services too. And not least it will divert some spending to US manufacturing. I think we’ll be surprised by the extent to which manufacturing turns up with a more competitive currency.

Reconsidering the American strip mall

This image and the text that follows are taken from Erik Hancock’s proposal to the Terreform ONE design competition for creating productive green space in cities, sponsored by the City of New York Parks and Recreation office and the American Society of Landscape Architects. This part of his proposal is called ‘Reconsidering the American strip mall‘ (large PDF file).

During the rapid postwar suburban expansion, thousands of small shopping centers- nondescript, one-story, automobile- centered buildings- sprang up across the United States. Eventually, the consumer’s appetite grew and the strip mall was superseded by larger shopping malls and regional ‘lifestyle centers’. Many strip malls now languish, solid but poorly maintained products of a now obsolete business model, the domain of high-turnover dollar stores and payday lenders.

Too ugly and vulgar for ‘respectable’ architects or preservationists, these buildings are in a kind of architectural limbo. When the design profession does address such an unlovely structure, the solution is almost invariably to knock it down and replace it with a new ‘green’ building. Sadly, what we fail to consider is that the embodied energy spent when a perfectly good old building is demolished is often far greater than any savings produced by the most sustainable new building. We tend to assume that the best solution to a problem is to clean the slate and start from scratch with a brand new concept- this is true of architects and urban planners alike. Instead of taking responsibility for the previous acts of the profession and cleaning up our mess, it is more exciting to declare a fresh, bold start free from those past mistakes.

This project makes the radical proposition that in fact, saving some of the ugliest and most problematic buildings represents our greatest opportunity to improve the built environment and conserve natural resources. These aging buildings sit in the heart of first-ring suburbs; they were designed to be simple and flexible. Architects as public servants need to take on a new ethical imperative – take these ‘bad’ buildings and help them to become beautiful, integrated, productive parts of the community.

For more information: http://googlegroups.com/group/project707

Risk of unilateral default/devaluation (crude but intriguing)

|

Indicator

|

Change between 2009 and 2010, %

|

||||||

|

variable

|

proxy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a

|

Growth outlook

|

real-effective exchange rate*

|

-0.3

|

-6.9

|

-3.6

|

-2.5

|

-2.7

|

|

b

|

Primary budget

|

primary budget/GDP**

|

6.3

|

-2.0

|

0.1

|

2.0

|

2.4

|

|

c

|

Continent liabilities

|

house prices***

|

-4.3

|

-15

|

-0.3

|

1.6

|

-1.0

|

|

d

|

Political pressure

|

unemployment rate**

|

3.0

|

1.1

|

0.4

|

0.8

|

1.7

|

|

Score

|

b+c-d-a (low=more risk)

|

-0.7

|

-11.2

|

3

|

5.3

|

2.4

|

|

|

Rank

|

1=highest risk

|

2

|

1

|

4

|

5

|

3

|

|

Tripe

|

| USA: Real-effective exchange rate |

I’m just astonished at the tripe which passes for sensible economic commentary right now. Take the WSJ 2011 outlook piece from 26 December. It ran in my city’s paper as part of a regular WSJ mini-edition, as it no doubt does in many city papers across the country.

The author tells us that although inflation is not a worry in 2011, the Fed’s balance-sheet expansion is storing up problems for later. This is written with the same authoritative, darkly somber tone that now seems to dominate conventional thinking about the Fed’s activities. It betrays an utter misapprehension of so basic a concept as the money supply.

Do these people think the “money supply” is what the Fed creates? It sure seems that way. They could not be more mistaken. The money supply is composed of everything which can be deployed as money. Most of this is created by the financial system. It is so far-reaching as to defy any reliable counting. But take it on faith that most of the broad money supply is not what the Fed creates. The Fed does create a special type of money, called ‘base money’. The banking system is required to hold this money, and the more of it that the banks hold, the greater their leeway to generate credit, which is money. This is presumably what has some people worried — banks are holding more and more of this special ‘base money’, and may one day use it to write legions of new credit.

In an economy with huge unemployment and excess capacity, that would be a great problem to have!

Returning to the WSJ 2011 outlook. What really got my blood boiling was the dark warning over the dollar’s external value. The author warns that, if the Chinese lose faith in us, they will stop buying our Treasury bonds and the dollar will “tank”. Who would not want this? Oh, yes. The financial services industry. They definitely don’t want a weaker dollar. And this is the WSJ after all. The US economy, on the other hand, wants it badly. We need the dollar to “tank”. We need to give our traded goods and services the level playing field they’ve been denied for so long. Our import-competing industries and our exporters have been getting short-shrift from the “strong dollar” policy since the middle 1990s. (A period which, incidentally, saw the rise and rise of financial services … to what purpose?)

And if a fall in the dollar translates into inflation … so much the better. Check your real interest rate time series and I’m sure you’ll agree.