We are promised by Shinzo Abe, Japan’s new prime minister, a three-pronged attack on deflation. Today, we saw one of those prongs: an easing in monetary policy. More on that in a second. But what I really wonder is whether we’re going to see the other two prongs: fiscal expansion and deregulation. It might be quite convenient to allow the Bank of Japan’s dynamism to weaken the yen enough to re-energise the traded sector, neatly circumventing any of the more politically difficult policies like higher spending and deregulation.

In Japan’s case, previous experiments with QE – admittedly not on the same grand scale – mainly served to boost exports without any significant impact on domestic demand. In a world where other nations are struggling for growth, a yen-induced export-led Japanese economic recovery might not be enthusiastically received.

If this is what happens, then Abe will have pulled a fast one — and precious little else will have changed. A big yen depreciation would juice up the economy plenty and, although it won’t be enough to achieve the 2% inflation target, it could easily reach the goal of turning mild negative inflation into mild positive inflation.

Now, about that monetary policy. The Bank of Japan’s policy communication (pdf) today reports that the Bank will double the monetary base over the coming two years. The monetary base is simply that part of the money supply over which the central bank has control: cash in circulation plus the banking system’s deposits at the central bank. It will use this increase to fund the purchase of a wider variety of assets: longer-dated Japan government bonds (JGBs) as well as equities through exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and real estate through Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITs).

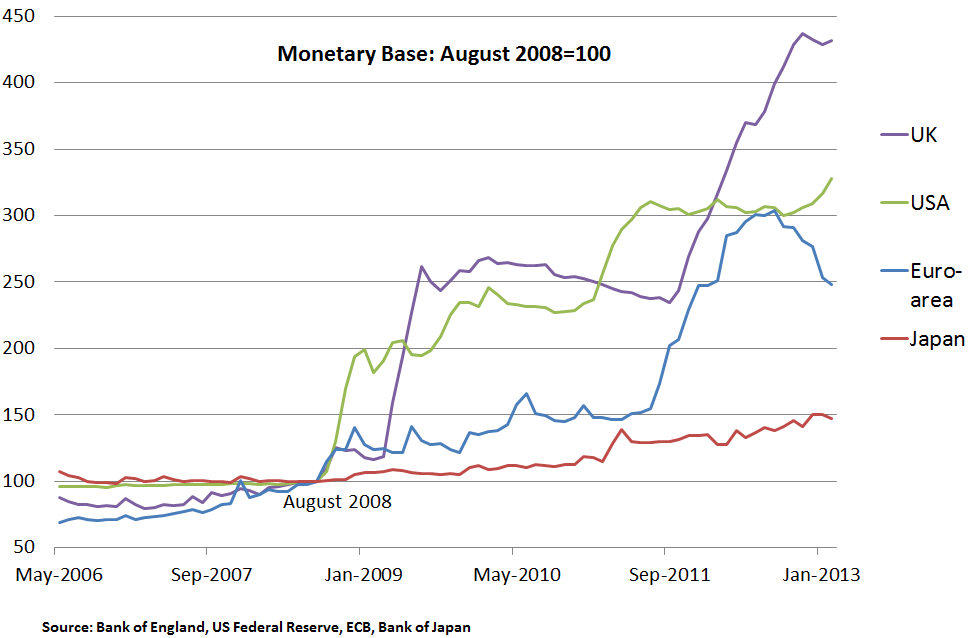

How radical is this “doubling” of the monetary base? Not that radical. The US central bank doubled the monetary base within five months of beginning its own form of quantitative easing (QE); the UK took ten months and the ECB took three years. In fact, since August 2008 (on the eve of the most acute phase of the financial crisis), Japan’s monetary base has only grown by half, while the UK’s has quadrupled and America’s has trebled. Does any of this matter? Probably less than you might think. With the private sector desperate to improve or maintain its financial position on a net basis, this policy remains akin to “pushing on a string” (as you-know-who put it).

Where it does matter is if such policies succeed in depreciating the currency (and it is not clear why they would, if the monetary base has no expansionary impact on broader money aggregates via the money multiplier, except through the perceptions of market participants, who may be over-impressed by whole-number multiples of base money supply).

Which brings us back to the real Abenomics. If all we get is a weaker yen but no serious fiscal expansion, the race is on to see who can impress the markets most with their central bank balance sheet growth. This is not how you’re supposed to deal with a global economic recession.